Blast Furnace Elisabeth

The Path to the Blast Furnace

To reach Elisabeth you left the general office by the corridor end door, followed a wide tarmac path leading underneath the works railway line (Highline) which then sloped gently up towards the staff canteen, a low white building. Passing the canteen on your left, bearing right, the road then sloped down and with the works canteen on the right, in front of you was Elisabeth and her huge, blue painted corrugated steel cast house. Continuing on down the hill brought you directly in front of the slag side of the cast house and the railway line where a trains of ladles known as ‘Slag Pots’ would be positioned.

The cast house floor itself was some twenty or thirty feet above ground level and was reached by wide metal steps leading to a gangway over the rails into a doorway cut-out. When the furnace was flushing, molten slag would simply pour from the runner-end spout and into an awaiting pot. Up in the cast house floor the slag ran along sand channels and a system of simple manually operated gates directed the flow towards each spout in turn. Once one pot was filled a gate would be dropped and the flow redirected along the channel for the next pot in the train below. Quite often a pot would be cracked and leak slag onto the line. This was dramatically but effectively dealt with by hosing the offending side of the pot with a jet of water creating a crust which formed a seal accompanied by clouds of steam. Once filled the train of pots would move away with crusts formed on top of the slag and wend its way to the tip at the Tarmac plant next to the steelworks, the railway line for the slag trains leading past the blast furnace office. Once at the Tarmac plant the diesel loco would uncouple from the pots, then couple to a chain connecting each one. The loco would then pull the chain tilting all the pots, emptying the molten contents down a slope to cool and be broken up later for use in road making.

The area around the blast furnace, ‘Elisabeth’, was fascinating for me. Built on large concrete foundations the furnace absolutely towered above. There were also the three tall hot blast (Cowper) stoves and lift tower for access to the furnace top to look up to. The gantry connecting the top of the lift to the furnace looked extremely high up and precarious. From the roadside you could either take the very broad metal staircase up to the cast house or another few steps down to the ground level around the base of Elisabeth for access to the hot blast stoves and the rear area. There was a constant hiss of compressed air, the shouts of men and rumble of machinery. Always around here too was a very distinctive and not unpleasant aroma. I don’t think I have ever smelt it anywhere else and I can only describe it as that of ‘oxide’. It must have been a combination of iron, coke, slag and everything else around…the scent of ironmaking.

If you ascended the flight of metal lattice steps, at the top you turned sharp left along another metal walkway and entered the cast house through a side opening in the panelling. This brought you directly next to the furnace with the slag notch and runner to the left, bustle main above and tuyeres in front. It was also gloomy with the very loud hiss of the blast along with the sound of rushing water which was visible, cascading down the bosh to keep it cool. If you walked around the furnace to the right you would come to an enclosed control room with a continuous row of narrow windows facing the furnace just to one side of the tap hole.

Within this cabin were all the instruments, dials and recorders for the furnace and was the base for the shift manager and leading hands. One instrument which always fascinated me was the stockline recorder which rested on the top of the contents of the furnace. I tried to imagine what it looked like inside…a mountain of coke, iron ore, limestone slowly shifting downwards sixty feet or so above a roaring and blazing incandescent mass…

At the far end of the cast house was a ramp in between the railway lines for iron and slag trains, for trucks to bring sand in an out. At the bottom of this ramp was a glass encased ‘No Entry’ sign which lit up and flashed when the furnace was casting.

Charging Elisabeth

If, instead of going up to the cast house, you descended a few steps below road level you would pass the base of the furnace on your left and the row of hot blast stoves to your right. (In the image below you have passed the stoves and so are now looking back : ‘highline’ on the left, skip hoist just behind you)

This would bring you around a corner, past the stoves, to the bottom of the skip hoist. I would often spend several minutes if the furnace was charging watching the skips going up and down the steep ramp. Standing at the safety handrail, if you looked down to the bottom of the hoist’s ramp, this is where the scalecar ran underground collecting its weighed charges (hence the name ‘scale-car’) from the bunkers above its track. The scalecar would deposit its charges of iron ore, coke, limestone, mill scale or turnings into the skip with loud rumbles. Suddenly the steel rope would tighten and the lower skip would start its ascent and rumble past you, whilst the one at the top which had its rear held up-ended would gently un-tilt itself and start to descend towards you. There was always a ‘thunk – thunk’ as the ascending skip passed by over a gap in the rails. I would watch it all the way to the top and as the empty one passed by the line would slow down as the full skip reached the tilt position and another rumble could be heard as its contents were discharged into a funnel shaped hopper closed at the bottom by the ‘small bell’. After each charge the small bell would open allowing the contents to then drop onto the ‘large bell’ which directly sealed the top of the furnace.

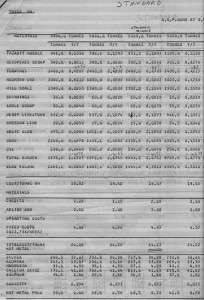

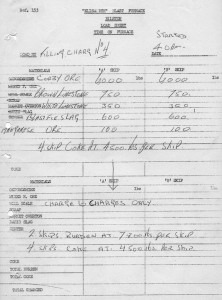

Each skip typically held 2,000 kg of coke or 3,500 kg of burden (ore, limestone, turnings, etc.). Coke, having a much lower density than burden, meant less weight in the skip for a similar volume.

After so many charges, with the small bell closed, the large bell would lower its contents into the furnace. You would know when this had occurred as the pressure relief valve opened at the very top of the furnace with a loud blast.

The top of the furnace also indicated when the furnace was temporarily ‘off blast’ for routine maintenance when a plume of steam would be visible. This would be the case usually one day per week.

Past the skip hoist was the dustcatcher on the left and the engineers – or ‘crash gang’ portacabins on the right. Memory fades now but continue walking and you pass open ground, maybe an unofficial car park, with the stockyards on the right. There was also a narrow pedestrian tunnel under the highline and stockyard which brought you out next to the blast furnace office with the other end near the general office.

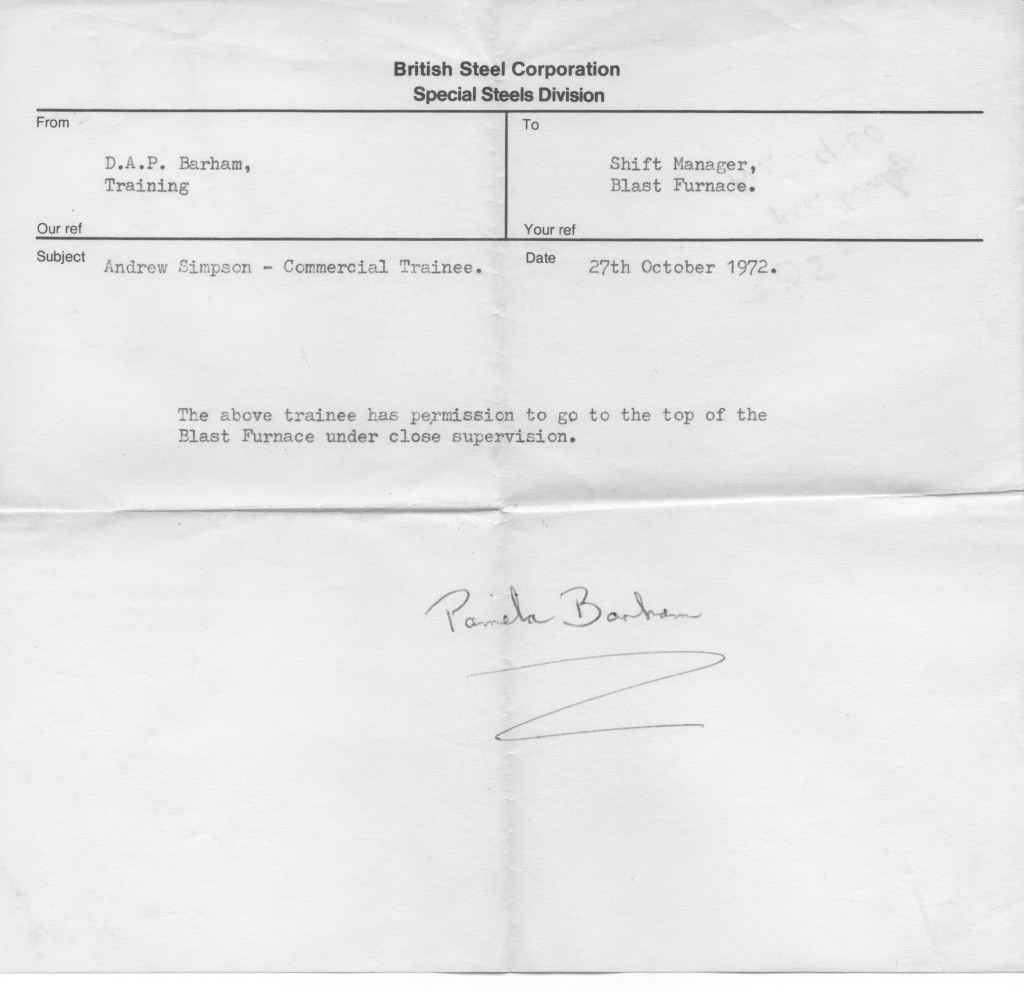

I was lucky enough to have three trips to the top of Elisabeth. The first occasion was the most memorable and took place before I was even in the Blast Furnace Department shortly after permission was given in late October 1972 (see memo right), escorted by Mr Woolley, the Assistant Manager.

Now one of the main dangers around a blast furnace is that of the deadly carbon monoxide (CO) gas – same as in a car exhaust – which is generated during the smelting process. This gas rises and becomes denser as you move higher up from the tuyere level. One of the furnacemen told me once of a man who passed out even on a gallery only just above the bustle main – so it is a serious business. Therefore in order to safely access the top the furnace must be “off wind” (or “off blast”) to ensure no gas is being generated and in the not so distant past it was common practice to take a caged canary along for early warning. On the appointed day Elisabeth was duly off blast with a tell-tale plume of steam issuing from a top valve. I met Archie at the entrance to the lift and once the door had been pulled closed it carried us both to the top gantry. I remember being very excited to take that ride up. As we stepped out we were on a small platform with narrow walkways to either the tops of the hot blast stoves to the right or the furnace top landing directly in front.

We walked across to the main furnace platform passing between the large gas offtakes and made our way carefully to the hopper and bell apparatus. An empty up-ended skip was held by the hoist rope at a crazy angle over the hopper, the insides of which intrigued me and became more visible as we ascended the external stairs next to the vertical gas off takes. Below the mouth of the skip could be seen part of the top of the small bell and the control rod assembly. The metal lattice stairs we were ascending were now to one side of the landing so you looked directly through them to the ground while climbing ever higher up the furnace…looking down was not a good idea…Eventually we got to the cross over where the central off take pipe connects with the downcomer – the huge pipe that takes the gas down to the dustcatcher. A further set of steps took us to the very top where the vertical offtake tops are closed off with valves. I remember these steps and handrails were even more greasy and dirty than the others. I noticed Archie did not use the handrails at all – I had no choice but to take a firm grip with both hands which took some washing once back on the ground! Finally we emerged on the top gantry with the wind now gusting hard accompanied by the loud hiss of steam. The view was quite fantastic with the entire works spread out below and vistas of Bilston and the surrounds beyond. I would have taken my camera but assumed photography would not be permitted. The journey down felt even more perilous but with care I made it back to tell the story !

My second visit with Sid Darby was more or less a repeat of the first (and just as good) however my third and final trip in September 1973, accompanied by Harold Pearson, was even more memorable because we did not use the lift but ascended via the metal stairs and walkways which ringed the furnace in successive galleries starting from the tuyere deck floor level. This was true adventure and not without some concern remembering those stories of men collapsing on the galleries unaware of the unseen and toxic CO gas which had overcome them. Of course the furnace was once again “off wind” so these areas were now temporarily safe but nevertheless I still took a deep breath passing through the NO UNAUTHORISED ACCESS gate at the bottom. It was fascinating to follow each walkway in circles ascending level by level, our footsteps ringing out as we rose ever higher. Eventually we emerged through the cast house roof into the open air pausing for a few moments to see the odd passing car and white helmeted workers below. We then crossed a walkway which connected with another series of stairs coming from ground level attached to the skip hoist. Finally we reached the main upper landing, level with the gantry to the lift. Again it was such a thrill to be on top and interesting to see once more the upper workings of the furnace close up along with the surrounding views of the works. Again, I wish I had had my camera with me since by then I had obtained permission to take pictures in the works, however I seem to recall that the opportunity came up on the spur of the moment.

A ‘Finger of Iron’ and Firearms Disposal

One day, when casting – and with prior agreement from the shift manager at the time – I pushed my finger into an area of sand surrounding the runners and the leading hand carefully poured molten iron into it using the long-handed sampling ladle. After cooling I had a finger of iron ! It was a fairly rough looking finger with a coarse surface but you could make out the joints and nail. Unfortunately this was lost along when I went to Canada in 1978 and my parents moved house deciding that such things were no longer required !

I never witnessed it but I was informed that on several occasions the police would bring a consignment of illegal firearms which had either been confiscated or handed in – usually following an amnesty. These were simply thrown into the iron ladles immediately before the blast furnace cast – all under heavy guard of course. The iron would soon cover them and as the ladle filled they would melt and diffuse into the pool of hot metal…

Cessation of Operations and Closure

I had long moved into Sales when Elisabeth was shut-down in the Autumn of 1977, originally only temporarily but never to work again. I had already left Bilston by the time the works closed so I have not included this period within my website – I prefer to remember when she was ‘alive’ and very much the ‘Queen of Bilston’.

Operational Documents

See below for a selection of various internal documents relating to Elisabeth – her Campaigns, raw materials, memoranda on operations and details of procedures to help give an insight into her running…

End of Second Campaign November 1962

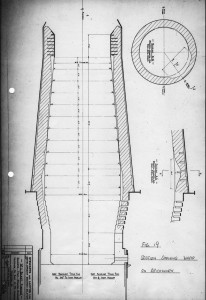

Cross section of Elisabeth showing the wear to the brickwork ining at the end of her second campaign.

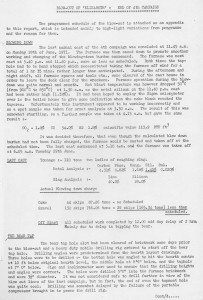

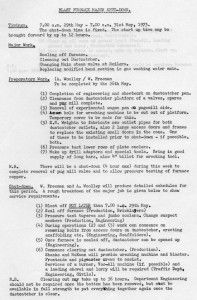

Blow Out of Elisabeth – End of 4th Campaign, June 1971.

First page of a report on the blowing out of the furnace at the end of her fourth campaign in June 1971. The ‘Bear tap’ referred to is the draining of residual molten iron which collected in the hearth below the tap-hole as a result of erosion over the period of the campaign. This was removed by drilling into the hearth below the cast house level and often yielded a hundred tonnes or more.

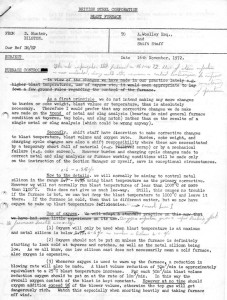

Memorandum on Operating Procedure

A draft memorandum from David Hunter in November 1972 to Archie Woolley and Shift Managers detailing how the furnace should be operated. Note David Hunter’s characteristic spidery handwriting !

Procedure for shutting down Elisabeth in May 1973

This was a planned shut-down in order to perform engineering work, principally cleaning out the dustcatcher which was well and truly “bunged up” (see DIARY MAY 1973).

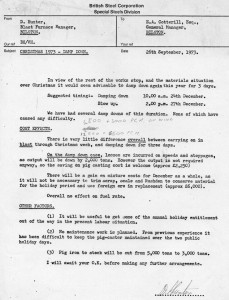

Plan to damp-down Elisabeth during the Christmas Period 1973.

A memorandum from David Hunter to General Manager, Eric Cotterill, outlining plans to damp down (effectively ‘switch off’) Elisabeth during Christmas 1973.

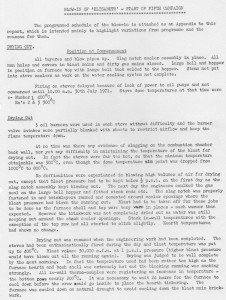

‘Blowing In’ : Start of Fifth Campaign

Extract from a report from the blast furnace department on the drying out procedure for blowing in Elisabeth in July 1971.

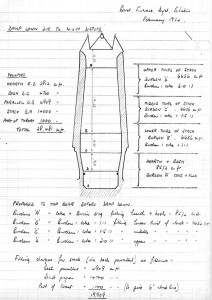

Cross Section of Elisabeth 1974

Diagram drawn up by Mr Woolley to show how Elisabeth was to be filled when damped down in anticipation of insufficient coke being available to maintain normal operations during the coal miners strike in February 1974.